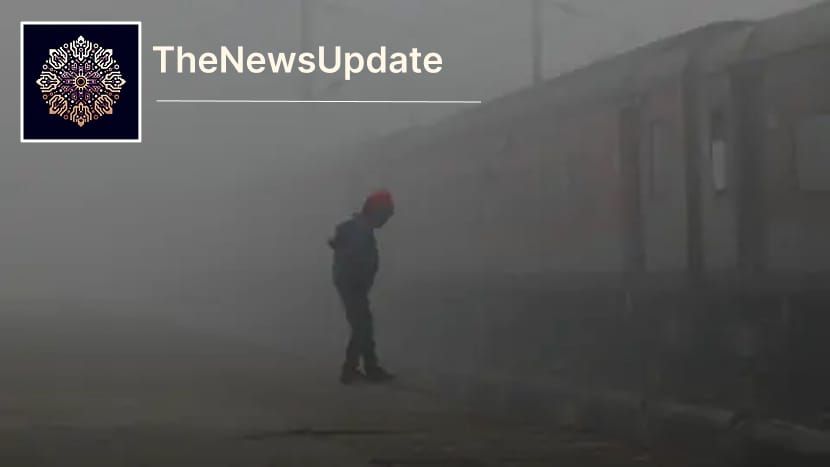

The phrase on every parent’s lips this winter is a fearful one: Delhi toxic air making children sick. As the capital’s skies thicken with grey haze and the Air Quality Index (AQI) stays stubbornly in the hazardous zone, paediatric clinics and emergency wards report a steady inflow of children with coughs, wheeze, breathlessness and recurrent infections. For many families, the last few weeks have been spent rushing to hospitals, buying inhalers, and wondering whether the damage done will ever be fully reversible.

Table of Contents

- Scale of the Problem

- Why the Pollution Worsens in Winter

- Immediate Health Effects on Children

- Voices from Clinics and Homes

- What Research Shows

- Practical Steps for Parents

- Policy Responses & What’s Missing

- Conclusion: A Long-Term Outlook

Scale of the Problem

Delhi’s air pollution problem is not new, but its intensity this season has pushed many families and health services to breaking point Delhi toxic air making children sick. The city’s AQI during recent weeks has frequently hovered between 300 and 400 — levels classified as “very poor” to “hazardous.” Fine particulate matter (PM2.5), tiny enough to penetrate deep into lungs and enter the bloodstream, has been the primary culprit.

When PM2.5 readings spike, hospitals report surges in admissions for respiratory problems. Paediatricians at busy clinics in and around the capital now say that a majority of young patients present with symptoms directly linked to poor air quality. In some clinics, doctors estimate the proportion of pollution-related respiratory cases rising from a typical 20–30% to nearly 50–70% during peak smog weeks.

Why the Pollution Worsens in Winter

The reasons the capital chokes every winter are multifaceted and, importantly, predictable. The main drivers include:

- Crop stubble burning in neighbouring states — large-scale burning sends a dense plume of particulates toward Delhi.

- Lower wind speeds and temperature inversion — cold, still air traps pollutants close to the ground.

- Vehicle emissions and industrial outputs — continued urban traffic and factory emissions add to the particulate load.

- Domestic sources — seasonal increases in space heating and the use of low-grade fuels in informal settlements.

These factors combine to create a toxic mix; the result is an environment where children — whose lungs and immune systems are still developing — are especially vulnerable.

Immediate Health Effects on Children

Exposure to polluted air has both immediate and cumulative health effects. In the short term, parents notice:

- Persistent coughing, wheezing and throat irritation

- Increased incidence of bronchitis and pneumonia

- Shortness of breath and reduced exercise tolerance

- Exacerbation of asthma and other chronic respiratory conditions

Paediatric pulmonologists warn that the immature lungs of infants and toddlers inhale more air per kilogram of body weight compared to adults — which means they absorb proportionally higher doses of pollutants. Repeated acute episodes, including severe infections that require oxygen therapy or nebulisation, may leave lasting impairments in lung function Delhi toxic air making children sick.

Voices from Clinics and Homes

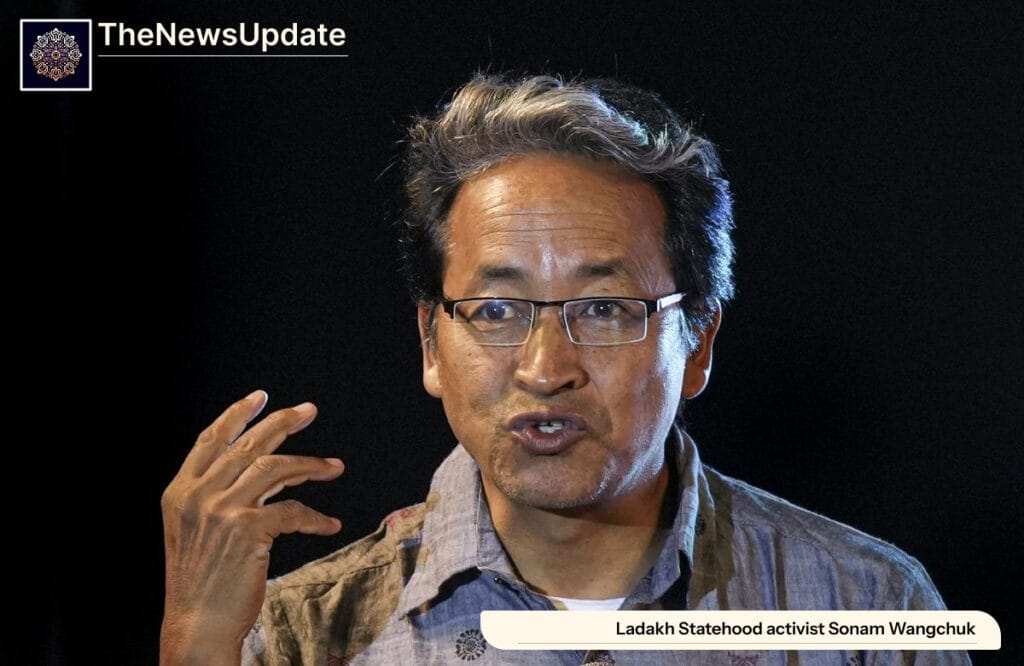

Frontline stories put a human face on the data. In Noida, a crowded paediatric clinic described by doctors as operating “at full stretch,” waiting rooms are filled with children clutching tissues and inhalers. Dr Shishir Bhatnagar, a paediatrician, told visiting reporters that the number of children with pollution-linked complaints has risen tenfold over recent years during the smog season.

Parents recount terrifying episodes: Khushboo Bharti remembers rushing her one-year-old daughter to emergency care in the middle of the night after a violent coughing fit that left the infant unresponsive. Following steroid nebulisation and oxygen support, the child was diagnosed with pneumonia. The memory of that night — and the constant fear when the child coughs now — illustrates the emotional toll the smog crisis exacts on families.

For many working-class households, the story is grimmer. Children living near busy roads, industrial clusters, or informal settlements face compounded exposure from outdoor smog and indoor pollutants like unclean cooking fuels and poor ventilation. For these families, the options are limited: they cannot simply move or keep children indoors indefinitely.

What Research Shows

Evidence from epidemiological studies links early-life exposure to air pollution with a range of long-term harms. Research indicates that children exposed to high levels of PM2.5 are at greater risk of stunted lung development, reduced lung capacity, and chronic respiratory disease in adulthood. Recent large-scale studies also connect certain air pollutants to increased risks of cognitive impairment later in life.

A University of Cambridge study of nearly 30 million people, for example, found associations between pollutant exposure and a higher risk of various dementias. While dementia is typically a disease of later life, the pathways of risk — chronic inflammation and vascular damage — often start with early, repeated exposure to harmful particulates.

The implications are stark: the current spike in pollution is not just a short-term public health nuisance; it potentially seeds chronic disease burdens that will surface decades from now.

Practical Steps for Parents

While systemic policy change is required to solve the root problem, families need immediate, practical measures to reduce risk. Health experts recommend:

- Limit outdoor activity during high-AQI days, especially strenuous exercise that increases inhalation of pollutants.

- Use N95 or equivalent masks for children over the recommended age and adults when stepping outdoors — they filter out most fine particulates.

- Keep windows closed when smog is worst; use air purifiers indoors if available (HEPA filters are effective for PM2.5).

- Maintain hydration and nutrition to support immune defence; ensure timely vaccinations and prompt medical attention for respiratory symptoms.

- Follow doctors’ advice for children with asthma or chronic conditions — have inhalers and action plans ready.

Experts caution that masks and indoor filters are mitigation, not cures. The only sustainable protection is cleaner air at scale.

Policy Responses & What’s Missing

Every year, authorities roll out emergency measures: restrictions on construction, temporary bans on older diesel vehicles, odd-even schemes and even cloud seeding efforts. While such steps can offer short-lived relief, they do not address systemic drivers such as agricultural burning, uncontrolled vehicular emissions, and lax industrial regulation.

Public health specialists and environmentalists repeatedly argue for a multi-pronged, long-term strategy:

- Regional coordination to curb stubble burning using viable alternatives and compensation for farmers.

- Cleaner transport — stricter emission standards, faster adoption of electric vehicles, and better public transport infrastructure.

- Industrial regulation — tighter emissions norms and real-time monitoring with enforcement.

- Affordable clean energy and better housing solutions for low-income families to reduce indoor pollution exposure.

- Public health readiness — better paediatric care capacity, early-warning systems, and school policies that protect children during high-pollution days.

Until such structural reforms gain political momentum, short-term measures will remain politically palatable but epidemiologically insufficient.

Conclusion: A Long-Term Outlook

The recurring summertime of smog and winter haze has made one thing painfully clear: Delhi toxic air making children sick is not an isolated seasonal discomfort but a public health emergency with long-term consequences. Children harmed today may carry reduced lung function and higher disease risk into adulthood, translating into future health burdens and economic costs.

Preventing that outcome requires commitment from multiple actors — regional governments, central authorities, farmers, industry, and citizens. Pragmatic short-term actions can reduce immediate harm, but meaningful protection for the city’s children depends on sustained policy change and enforcement Delhi toxic air making children sick.

For parents like Khushboo and others who have watched their children struggle to breathe, the hope is simple: a city where playgrounds are safe, schools can remain open for outdoor play, and a cough no longer triggers panic. Until then, families will continue to adapt, shield and advocate — hoping the air clears, and the next generation can breathe a little easier.

Follow for latest updates The News Update