By The News Update— Updated Nov 13, 2025

Summary: What Happened in Mulund?

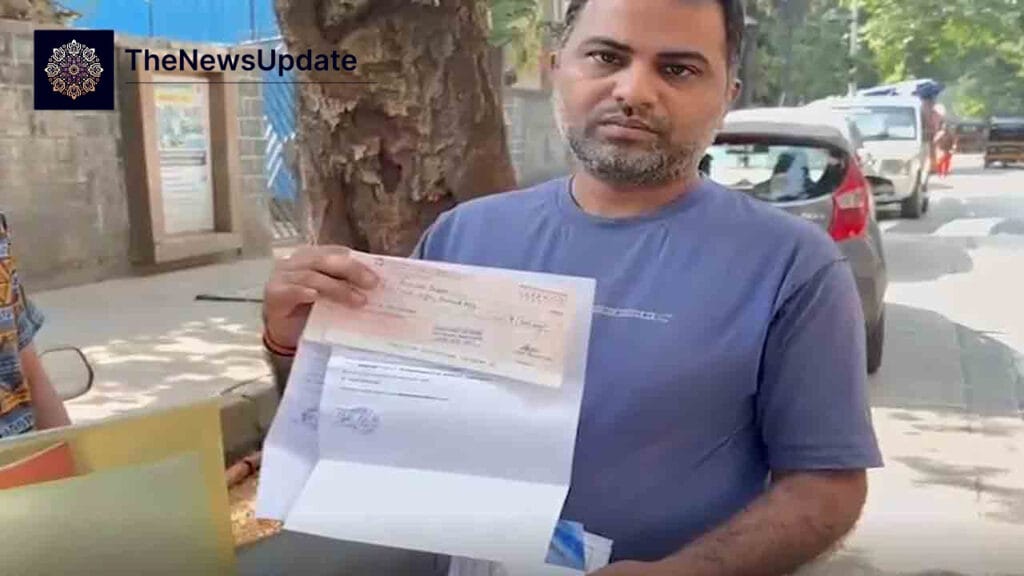

A pani puri vendor in Mulund, Mumbai alleges he was defrauded of Rs 3 lakh after being shown a bogus sale agreement for a stretch of public footpath. The vendor, Santosh Bachchulal Gupta, says he paid Rs 50,000 in cash and transferred Rs 2.5 lakh via RTGS in 2023 to a local Shiv Sena leader, Avinash Bagul, for exclusive use of the pavement space — only to discover later that the space belonged to the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) and was not Bagul’s to sell.

The case — widely reported and now a subject of political and civic outrage — raises questions about the criminal misuse of political influence, the vulnerability of street vendors, and the governance of Mumbai’s public spaces. This story examines the allegations, the responses from the accused and the party, the legal steps taken so far, and the wider implications for vendor rights and municipal oversight.

Timeline: Money, Cheques and Broken Promises

According to Gupta’s account, the arrangement was finalised in 2023. He says he handed over Rs 50,000 in cash immediately and completed an RTGS transfer of Rs 2.5 lakh. Gupta claimed that Bagul later issued an old cheque and then two additional post-dated cheques — all of which bounced.

- 2023: Gupta pays Rs 3 lakh (Rs 50,000 cash + Rs 2.5 lakh RTGS) for the alleged “sale” of footpath space in Mulund.

- 2024: Gupta realises the space is under BMC jurisdiction and that Bagul had no legal title to sell it.

- Early 2025: Gupta approaches local police. Bagul issues cheques that bounce. Police advise Gupta that a court order may be needed to proceed further.

- Nov 2025: The case gains media attention; local Shiv Sena leadership announces an internal inquiry.

Gupta has told reporters he financed the purchase by taking a bank loan and pledging his mother’s gold jewellery as collateral — a personal cost that has amplified the alleged injustice.

Allegations Against the Sena Leader

Gupta’s charges are stark: he says Bagul executed a bogus sale agreement for a piece of public property and accepted payment under false pretences. If the allegations are substantiated, they would indicate fraud, breach of trust, and possibly elements of criminal misappropriation.

Key allegations include:

- Fraudulent sale of public land (footpath) that does not belong to Bagul.

- Accepting large payments (cash + RTGS) without transferring possession or title.

- Issuing post-dated cheques that later bounced, suggesting an intent to defraud.

- Pressure on a small vendor who financed the purchase through loans and family collateral.

Accused Leader’s Response and Party Inquiry

Avinash Bagul, the Mulund-based leader associated with the Eknath Shinde-led Shiv Sena faction, has denied the allegations. Bagul told reporters that there was no “sale agreement” and that the money was a loan he had already repaid in cash. He dismissed the claims as politically motivated, according to his statement to the media.

With the controversy escalating, local Shiv Sena leadership said it would probe the matter. Jagdish Shetty, the vibhag pramukh, said the party had asked him to inquire and promised that “no injustice should be done to anyone.” The party’s internal review—if conducted transparently and promptly—could be a first step toward establishing facts; however, critics warn that internal probes risk being perfunctory without independent oversight.

Legal Status: Police Action, Bounced Cheques and Court Orders

Gupta approached the police after repeated failed attempts to get either the space or a refund. He says the police told him to obtain a court order before a formal investigation could proceed — an instruction that highlights the procedural hurdles many complainants face in cases involving influential accused parties.

The fact that multiple cheques issued as repayment bounced strengthens Gupta’s civil claim for recovery and supports potential criminal charges such as cheating and criminal breach of trust, depending on the evidence. However, policing agencies have so far moved cautiously. Legal experts note that victims in similar matters often face a long wait for redressal, especially when accused persons claim the transactions were informal loans.

Why Footpath ‘Sales’ Happen: The Mumbai Context

Mumbai’s pavements have long been contested spaces. Municipal failure to formally allocate and enforce street-vending regulations creates a gray market where influential actors or local strongmen can exploit vendors. Vendors seek exclusive spots for livelihood; middlemen or local political figures sometimes exploit that demand by offering “arrangements” for a fee.

Factors enabling such scams include:

- Weak municipal oversight and slow enforcement by the BMC.

- Lack of clear, affordable licensing options for street vendors.

- The presence of intermediaries who claim de facto control over public spaces.

- Vendors’ vulnerability due to poverty, lack of legal knowledge, and urgent capital needs.

For a city that prides itself as India’s economic capital, recurring episodes of illegal pavement sales raise uncomfortable questions about governance and rule-of-law at the grassroots level.

Human Cost: A Vendor’s Livelihood and Family Security

Gupta’s personal story underscores the human cost. Forced to secure a bank loan and pledge his mother’s jewellery, he now faces both financial stress and the loss of expected income from the alleged “purchase.” For street vendors, access to a prime spot can mean the difference between survival and debt; losing both money and the promised space multiplies the harm.

Advocates for street vendors stress that informal transactions driven by desperation are predictable outcomes when official channels for vending are inaccessible or poorly managed. This case, they say, is symptomatic of a broader systemic failure to protect the urban informal workforce.

Role of Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC)

The BMC is the legal custodian of Mumbai’s public footpaths and spaces. In theory, any allocation, licensing, or eviction must be coordinated through municipal procedures. Gupta’s discovery that the space he “bought” was BMC property points to criminal misrepresentation rather than a contractual sale.

Municipal authorities have previously undertaken periodic drives to regulate street vending, including issuing identity cards under the Street Vendor Act and designating vending zones. But critics argue that implementation is patchy, and unauthorized intermediaries continue to monetize the gaps.

Political Fallout and Media Attention

News of the alleged scam has reverberated across local politics. Opposition parties and civil society organizations seized the opportunity to criticize both the accused and the political culture that allows such incidents. Social media amplified Gupta’s plight, drawing public sympathy and calls for a swift judicial probe.

Media coverage has also pressured the Shiv Sena leadership to act. Whether the party’s internal inquiry will lead to concrete disciplinary measures or a referral to law enforcement remains to be seen. Public pressure may also push police to more actively pursue the case and seek a judicial remedy for Gupta.

Legal Remedies and What the Vendor Can Seek

Gupta has several legal pathways available:

- Filing a criminal complaint for cheating and criminal breach of trust, supported by payment receipts and bounced cheque records.

- Pursuing a civil suit for recovery of money, backed by documentation of RTGS transfer and cash payment evidence.

- Seeking interim protection orders from courts to prevent the alleged accused from disposing of assets.

- Leveraging public-interest or vendor-rights groups to secure legal aid and media attention.

Legal advocates note that evidence preservation — bank receipts, witnesses, and any written communications — will be crucial to securing a favourable outcome for the vendor.

Policy Lessons: Strengthening Vendor Rights and Municipal Oversight

This case surfaces clear policy lessons for Mumbai and other Indian cities:

- Strengthen licensing & transparency: Make vendor licensing faster, cheaper and more transparent to reduce dependence on intermediaries.

- Improve grievance redressal: Create single-window systems for vendors to report fraud and get quick remedial action.

- Protect vendors financially: Provide microcredit and formal financial products that reduce the need for risky informal transactions.

- Enforce municipal ownership: Regular public listings of legally allotted vending spots and robust monitoring to prevent illegal “sales.”

When municipal institutions work proactively, the market for illegal sales shrinks — and the everyday livelihoods of small vendors are better protected.

Voices from Civil Society

Street-vendor advocacy groups reacted with concern. “This is a recurring pattern where political muscle rents public space to the vulnerable,” said a representative from a local vendor rights NGO. “We need quick legal recourse for victims and better institutional protection for vendors.”

Legal experts urged a speedy criminal probe and suggested the BMC compile and publish maps of legally allotted vending zones to increase transparency and prevent future scams.

Related Coverage and Sources

Conclusion: Accountability, Redress and Reform

The Mulund pani puri seller’s allegation of being duped for Rs 3 lakh by a politically connected actor strikes at multiple fault lines: the desperation of street vendors, gaps in municipal governance, and the potential misuse of political influence. For Santosh Gupta, immediate justice means recovery of his money and access to the space he believed he had purchased. For the city, it means closing the loopholes that let such scams persist.

Whether through police action, judicial orders, internal party inquiry, or civic pressure, the case will test Mumbai’s capacity to protect its most vulnerable workers and to hold powerful actors accountable. In the meantime, the incident stands as a reminder: public spaces are public assets — and no one should be able to sell what does not belong to them.

Reporting note: This article is based on reporting by local journalists and statements from the vendor and accused. For original reporting on the case, see India Today and local Mumbai coverage.